Subsections to this chapter:

I have now set forth the two major cases of attractions, namely when the centripetal forces decrease in the squared ratio of the distances or increase in the simple ratio of the distances, causing bodies to revolve in conics, and composing centripetal forces of spherical bodies that decrease or increase in proportion to the distance from the center according to the same law — which is worthy of note.

– Isaac Newton, The Principia: Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy

With that, Sir Isaac Newton wrote one of the greatest understatements of all time. For those not accustomed to reading the works of Newton, or unfamiliar with how mathematics and physics reads when written in English, the Newton quote above is undoubtedly a challenge to understand. Roughly translated, that quote is the original scientific description of how planets revolve around the sun, which Newton thought was “worthy of note.”

Worthy of note? I should think so!

At the time of Newton, this notion that we all now take for granted, was still a somewhat novel, and more than a little controversial, concept. Well before Newton, Nicolaus Copernicus earned his fame as the Renaissance-era astronomer who proposed the notion that the sun was the center of the known universe, and everything else revolved about it. He was reluctant in promoting his work, knowing it would be scorned by some as heretical. Following Copernicus, Johannes Kepler advanced our knowledge in orbital mechanics with three Laws of Planetary Motion. He avoided scrutiny by asserting that the mathematical simplicity and beauty of his discoveries were a testament to a divine order established by God. Following Kepler, Galileo Galilei noted how the moons of Jupiter orbited around their host planet with his newly invented telescope. His advocation for heliocentrism, the notion that the Earth orbits the sun (and maybe a fair bit of independence from the church), led him to be arrested by the church for heresy in 1633. It was Newton’s 1687 work that finally provided the mathematical proof of gravitational laws that govern the planetary motion. These formulas would stand as the comprehensive explanation for this phenomenon until Einstein came along 220 years later when he reasoned that gravity wasn’t so much an attractive force, but rather a distortion of the spacetime continuum. It’s a subtle shift in perspective, but one with profound repercussions that are suitable for exploration in books other than this.

Nevertheless, when Newton modestly confessed, “If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants," it is clearly a nod to Galileo, Kepler and Copernicus who made great advancements in orbital mechanics. Is that where it ends? The notion that Earth is the center of the universe dates back to Ptolemy and the ancient Greeks. Was Copernicus the first to be inspired with an epiphany that this could be wrong? Copernicus was one of the first scientific names of the Renaissance to emerge from the so-called “Dark Ages”. During this period of European stagnation, there was relatively little in the way of scientific development. Thankfully, the Arabic scholars were busy during this period. During the 14th century Ala al-Din Abu'l-Hasan ali ibn Ibrahim ibn al-Shatir developed the most accurate models to date of celestial objects’ movements, relying entirely on empirical observations. While his model was still geocentric (everything orbits around Earth), it is notable that it was mathematically identical to that of Copernicus. Al-Shatir was the student of Nasir al-Din al-Tusi who led the efforts to build a state-of-the-art observatory. After about a decade of observations, he published a method of describing planetary orbits that al-Shatir later built upon, and a catalog of the night sky, with astronomical tables that calculated the positions of the planets and stars. Before him, Omar Khayyaam established during the 12th century the most accurate solar calendar of his time – even more accurate than the European Gregorian calendar that would be produced some 400 years later. Before Khayyaam, 10th century al-Battani was making advancements in orbital mechanics. He improved the accuracy of the definition of the solar year and is known for having advanced various concepts of trigonometry. His influence on the European renaissance is well founded in the fact that he was cited by Copernicus 23 times. With Copernicus clearly aware of the mathematical similarities between his work and that of al-Battani and al-Shatir, it begs the question as to how much of Copernicus’ work was original - but that’s a debate for another time. Of course, all of that discussed here rests upon the work of Muhammad ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi in the ninth century, who was the first to develop a rigorous method for calculating the value of unknown variables by balancing the known and unknown quantities on either side of an equation. He published his work in a book entitled “The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing”. Of course, he didn’t name it in English. The original Arabic name was “Al-kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī ḥisāb al-jabr wa’l-muqābala”. As this is quite the mouthful, the book was commonly referred to by a shortened name: Al-jabr, which translates to “reunion of broken parts”. Maybe you have come to recognize by this point, that al-Khwarizmi is known today as the father of Algebra.

Newton is celebrated as one of the greatest – if not the greatest – scientific minds humanity has ever seen, and not without good reason. There is a compelling argument to be made that he is deserving of the title. However, it is clear that he benefited from learning from a long line of people who learned from those who came before them. The giants upon whose shoulders Newton stood were themselves standing on the shoulders of giants. Building our knowledge on the foundations handed down throughout time enabled the development of observational and analytical tools and set the stage for Newton to pull it all together.

Giving Newton his due credit, I would argue there’s one critical person missing from this discussion. In between the contributions of the aforementioned were the development of one of the most important advancements in human history that doesn’t grab headlines, but without which, significant advancement would have been impossible. This honor goes to Sir Francis Bacon and his formalization of the scientific method. Had Bacon not published Novum Organum Scientiarum, (New Method of Science) which defined the rigorous process of going about understanding the world through observation and testing, Newton might never have become a household name.

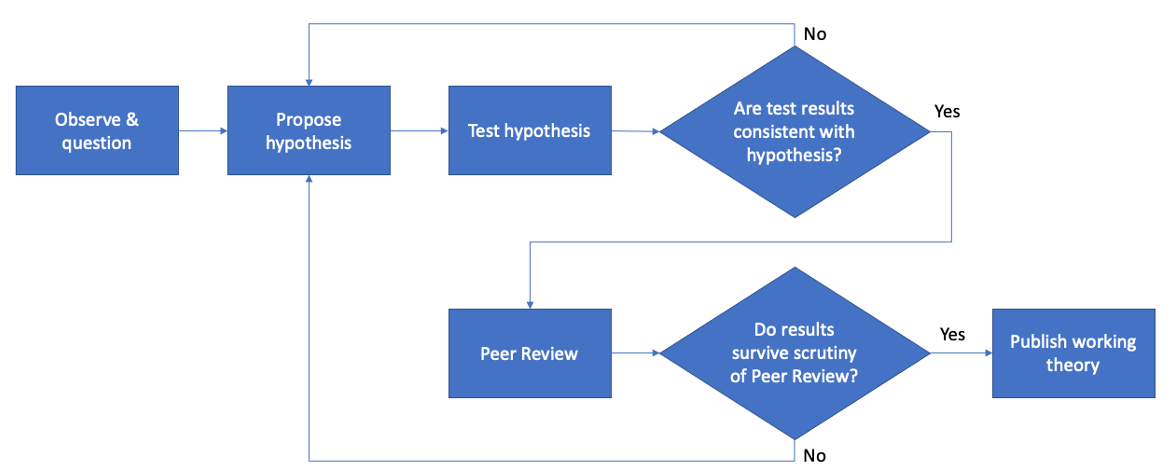

The scientific method can be described by the following flow chart:

Why would the development of the scientific method be one of the most important advancements in the history of humanity? Before the advent of charting a path forward based on a rigorous scientific perspective, humans explained the world through the lenses of myth, legend and religion. While this is the best that early man could do, it is not an effective foundation. When your medical technology is based on blood-letting and leeches, you’re not likely to significantly increase the survival rate of your society. When the success of your crops is believed to be dependent upon sacrificial offerings to Ceres, you’re not likely to be focused on the things that might actually improve your crop yield. One could therefore make the argument that Sir Francis Bacon deserves the credit for all of humanity’s scientific advancements.

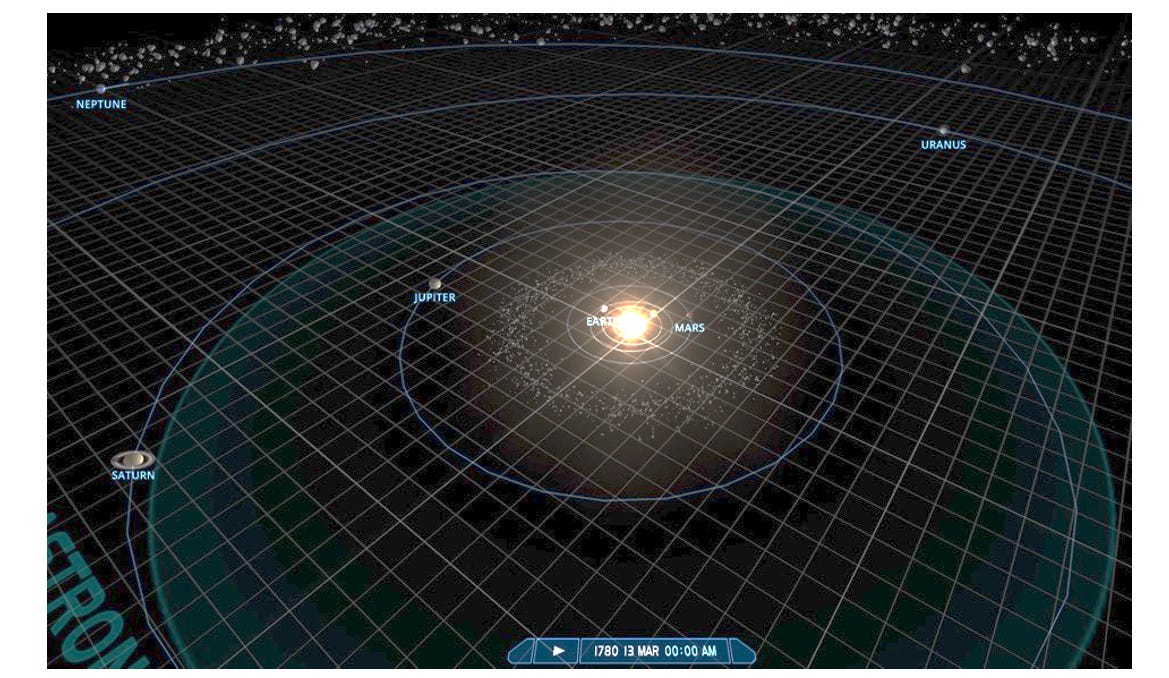

To illustrate the power of the scientific method, take the discovery of the planet Neptune as an example. If those in charge of naming newly discovered planets weren’t so preoccupied with Roman gods, I would argue that the planet we know as Neptune should have been named after Bacon. All the planets between Mercury and Jupiter are visible to the naked eye and are therefore likely to be assigned names well before Bacon. Those discovered afterward, however, are prime candidates for honoring those who enabled their discovery. Uranus had been discovered by William Herschel essentially by accident in 1781. Why they chose the unfortunate butt of sophomoric jokes is the study of a different book. Nevertheless, thanks to the wonderful website www.solarsystemscope.com, we can see how the planets were aligned at that time:

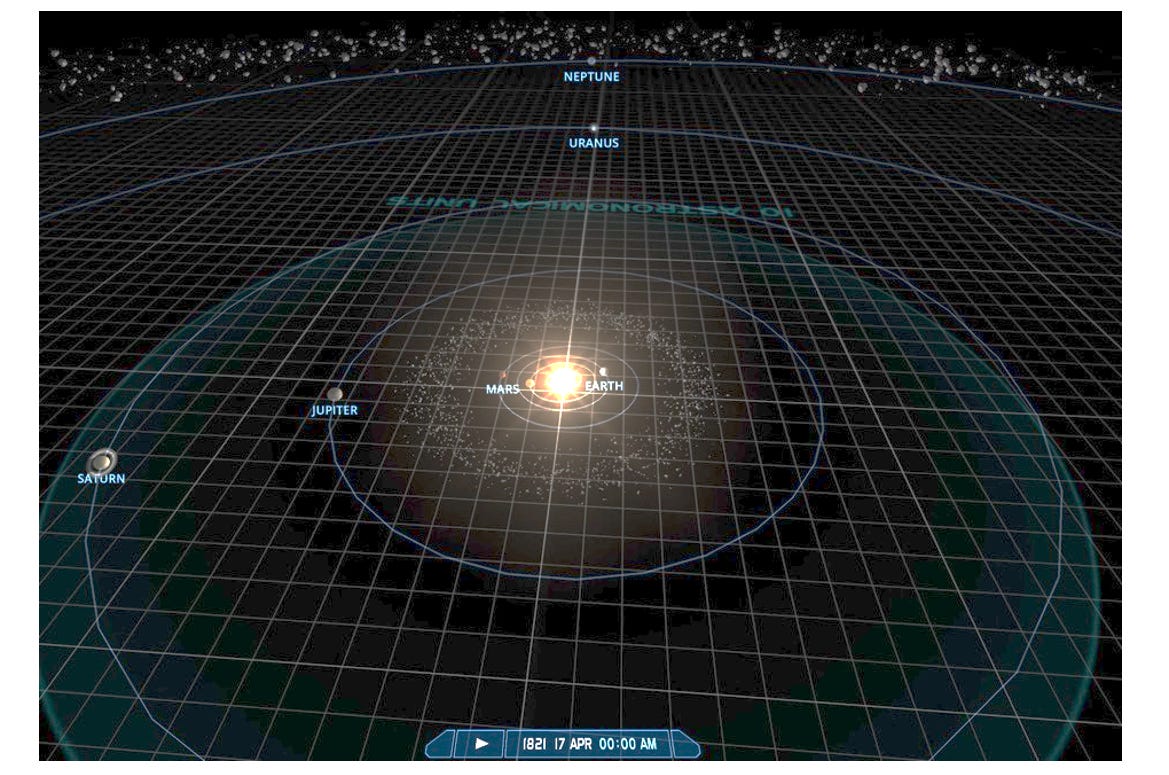

Because planets closer to the sun orbit faster than those further away, Uranus was catching up to Neptune. It wasn’t until 1821 that it finally caught up:

That’s when astronomers noticed something unexpected. The orbit of Uranus wasn’t following the orbital mechanics defined by Newton. What does an astronomer do upon realizing this? Double check their measurements. Once the double checks are confirmed, what are we left to conclude? Maybe Newton was wrong? Hard to make that accusation when so much of the rest of the solar system matched Newton’s formulas so well. Who wants to be the person to go up against Sir Isaac Newton? If you take a shot at the King, you best not miss. So, you carefully explore other possible reasons for Uranus to deviate from the orbit predicted by the King. Maybe something massive nearby is providing a gravitational tug on Uranus, sending it into an unusual orbit? That could do it!

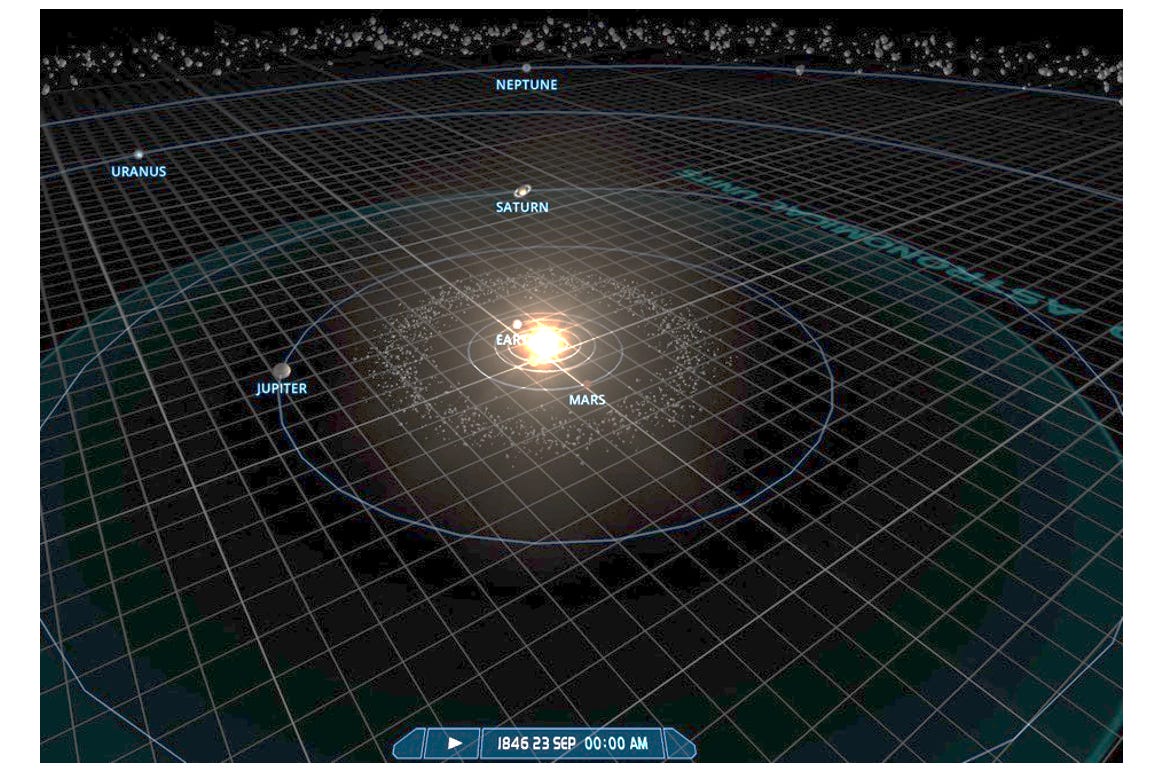

By the time 19th century astronomers developed this hypothesis, it was evident that if there was another planet further out from Uranus, it would, by this time, be lagging behind Uranus. Astronomers Urbain Le Verrier and John Couch Adams had independently calculated the position of the hypothesized planet. Finally, on September 23, 1846, German astronomer Johann Gottfried Galle trained his telescope to the predicted region, and indeed, found a point of light that was moving relative to the otherwise static backdrop of stars. A new planet was discovered! The only reason it was discovered was that astronomers were directed to a specific portion of the sky in search of a yet-to-be-discovered planet. The only reason why they were directed there was the fact that Uranus wasn’t behaving as science had predicted. In fact, the only reason Neptune was discovered when it was is thanks to the scientific method!

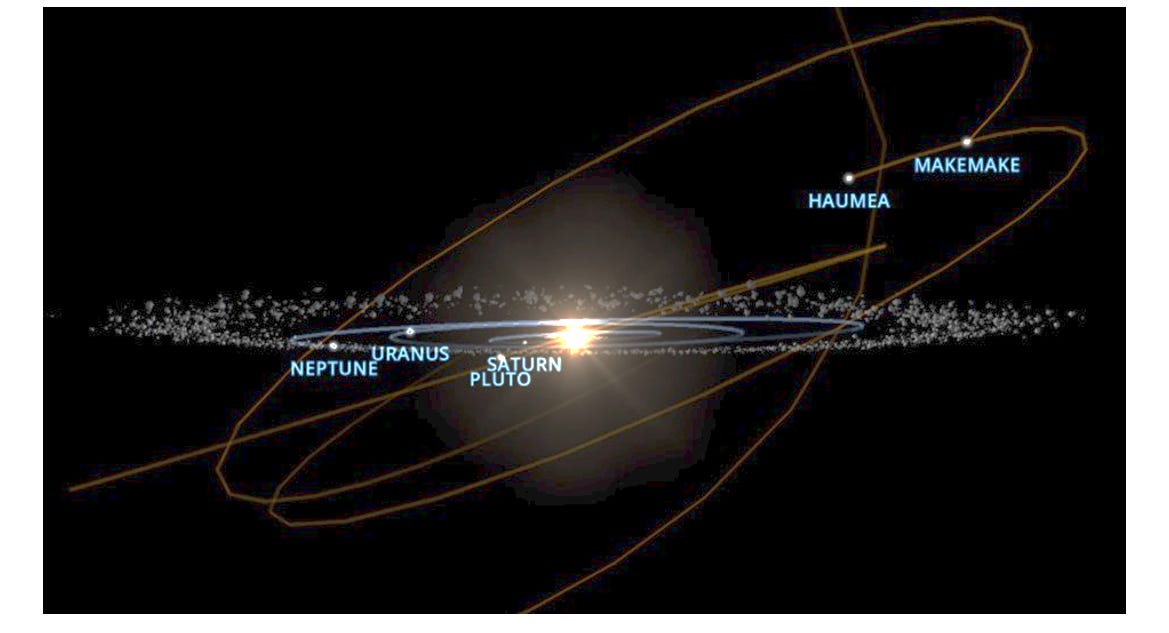

It's serendipitous that Uranus was accidentally found when it was. Had it been discovered after 1821, we might not have noticed the irregular orbit until the next time Uranus and Neptune came close together: 173 year later, in 1994. This timely discovery leads us to some of the discussions going on today: The primary solar system is all on the same plane – except for some of the dwarf planets (Pluto, Haumea, Makemake) on the outer edge of the known solar system. Turns out, their orbit is on an unusual tilt:

These unusual orbits don’t contradict any theories, but it does make one wonder why they’re so different from the rest of the solar system. Could there be another planet out beyond Neptune that is disrupting their orbits, similar to the disruption that Neptune had on Uranus? The search for the next planet is ongoing as I type this. This is the nature of the scientific method. An unexpected observation leads to a hypothesis, which leads to tests, scrutiny and ultimately acceptance as a theory – until it is debunked and refined after new, contradictory, evidence is presented.

So, we have the scientific method, and most liberal arts colleges offer courses in political science. You’d think that the two would work well together, just as the scientific method has worked for other sciences. If ever there was a course of study that needs the scientific method, it would be political science – the study of how humans govern. dropped balls behave according to a formula. Planets orbit stars according to a formula. Electrons orbit an atom’s nucleus according to a formula. But people? We’re messy. We’re emotional. We’re at times illogical. The need to employ the scientific method in politics is even greater than in other sciences in order to cut through the bullshit humans introduce when dealing with each other. Alas… it’s nowhere to be found.

How do we apply the scientific method to human behavior? A ball falls to the Earth in a predictable manner regardless of which ball you drop, or where you drop it. Give a person a tax cut, and one person will put their savings in the bank, while another person will go on a spending spree. One cannot simply apply the scientific method based on the actions of a single person, but it is absolutely applicable to how society works as a whole. In the aggregate, the peculiarities of outliers are overshadowed by the readily discernable trends of the majority. As a collective, humans tend to act in predictable ways that can be observed and then predicted for the future.