This interview was going to be unlike any other. The conversation started under the assumption that it would follow the typical script. Unbeknownst to seemingly everyone but the guest, the show’s script was scrapped from the get-go.

“Can I say something very quickly? Why do we have to fight?”

The laughter from the studio audience revealed how ridiculous the question was. CNN’s Crossfire was all about the fight. Pick a topic, surround a spokesperson for the topic with professional partisans – one from the conservative right and one from the liberal left – and let the nastiness begin. This modern-day version of the gladiator match had entertained audiences for years with the bickering and the indecipherable shouting over each other. Nobody ever gets to claim victory in the end. The show is more of a cathartic release for viewers on both extremes of the ideological spectrum to get juiced up by listening to the side they most identify with. Wind them up and let them flail against their “opponent”. How satisfying is it to watch someone whom you’d like to punch in the nose get verbally jabbed throughout the episode? But Jon Stewart was serious.

“Why do you argue, the two of you?”

Again, the laughter from the audience was the telltale sign that the audience wasn’t yet up to speed with Stewart’s intentions. What they thought was a joke wasn’t a joke at all.

“So, I wanted to come here today and say... Stop.”

More laughter from the audience. Stewart’s stage was not yet set. Speaking of politicians:

“You're not too rough on them. You're part of their strategies. You are partisan… what do you call it … hacks.”

Jon Stewart, host of The Daily Show on Comedy Central was being interviewed on CNN’s Crossfire by former advisor to Bill Clinton, Paul Begala and conservative commentator, Tucker Carlson. Stewarts impeccable comedic timing produced more laughter. It went on like this for some time, producing laugh after laugh, until Stewart dropped the comedic pretense to make his point. In this pivotal moment, everyone, hosts included, finally realized the joke is on them. From the transcript of the October 15, 1982 show:

STEWART: You know, the interesting thing I have is, you have a responsibility to the public discourse, and you fail miserably.

CARLSON: You need to get a job at a journalism school, I think.

STEWART: You need to go to one. The thing that I want to say is, when you have people on for just knee-jerk, reactionary talk...

CARLSON: Wait. I thought you were going to be funny. Come on. Be funny.

STEWART: No. No. I'm not going to be your monkey.

Realizing they have an entirely different interview on their hands than the one they imagined, Begala and Carlson cut to a commercial break to regroup. They had a problem on their hands: Stewart was not buying into the prescribed format of the show, refusing to proffer up red meat to the salivating partisan lions.

This episode has gone down in television history as one of the more memorable episodes of Crossfire, but provides the impetus for a profound question. If you put, over the course the many seasons that Crossfire had aired, a multitude of topics under the scrutiny of debate by experts, one might expect that eventually it would produce a “winner”. A forum such as this might actually identify one side emerging with the clearly superior position. Rarely, if ever did this happen. Impassioned debate ensued, and at the end of the episode, political junkie viewers on both sides took from it what they wanted, and they moved on to the next show in the CNN lineup for the evening. Crossfire was the quintessential example of political masturbation. It feels good to engage in it, but ultimately, nothing ever comes of it. No one ever had their views changed. Nobody ever conceded that the other side was correct. It was aired on a news network, but make no mistake: it was all spectacle in the battle, with little concern over the outcome. That’s fine for television entertainment, but it raises the question:

Is there political truth?

When you pit two ends of the political spectrum against one another to debate their views on a topic, you would hope to distill some political truth from the exercise. Is abortion actually murder of babies, or a medical procedure that every woman has a right to have? Does gun control infringe on our Second Amendment rights, or is it an effective means to protect innocent people in society? Do tax breaks that favor the wealthy and corporations benefit society, or are they just a giveaway to the special interests that fund political campaigns? Is heath care a human right that society should fund, or do individuals need to fend for themselves in order to obtain medical care? This is but a sample of the current political debates and one might imagine that there should be definitive answers to each of these. Yet, Americans been debating each of these for generations. Roe v. Wade was decided in 1973 after many decades of debate. 50 years later, it was overturned (during the writing of this book) thanks to Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization. Roe, followed by Dobbs illustrates the complete inability of Americans to establish any sort of political facts. It’s illegal… because a few people in black robes said so. Wait, now it’s legal… because a few people in black robes said so. Wait now it’s illegal again… because a few people in black robes said so.

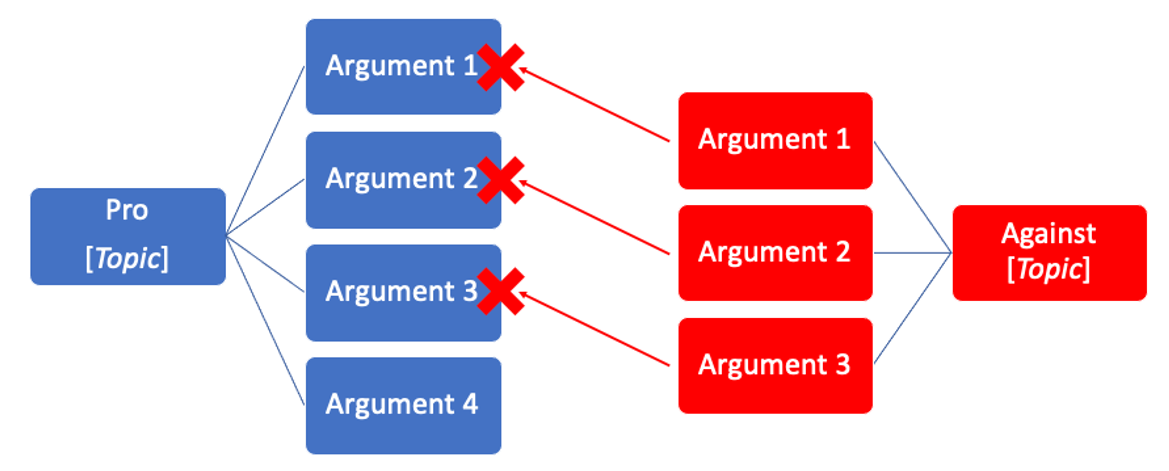

But by all means – let’s tackle the complexities of human existence in the 22 minutes between commercials of a half-hour show, where there isn’t nearly enough time to delve into the nuances of any particular topic. Crossfire, as aired, was never going to produce a clear-cut winner, but it could have, if it were structured in a way that produced meaningful dialogue. Ideally, one could chart out the arguments on each side of the debate resulting in a diagram that looks like:

In this case, if the expert in support of the topic was able to present an argument for which the opposite side didn’t have a rebuttal, one could reasonably conclude that the argument in support of the topic carried the day. From a political science perspective, it’s unfortunate that a show like Crossfire, which tackled prominent topics of the day, wasn’t equipped to draw such a conclusion. Conversations meandered without conclusion. Non sequitur conclusions were not dismissed. Thoroughly rebutted arguments were reanimated to rejoin the fight later on. In short, it was merely entertainment for the consumption of political junkies on both sides of the political spectrum to take from it what they will, and CNN took the ratings to the bank. From a political science perspective, no political truth was every established from watching the show.

This book is based on the premise that there is such a thing as a political truth. Or, at least, a political theory.

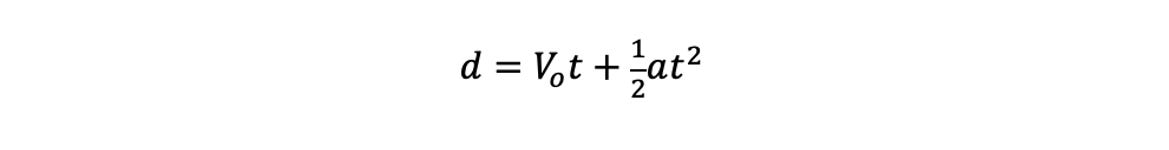

In the realm of science, there is no truth – only theory. If you hold a ball out at arm’s length and release it, what do you expect will happen? The ball will fall to the ground, of course. You might think that something as basic as this would rise to the level of truth. Alas, there is only the theory of gravity, which predicts that the ball will fall to the ground, governed by the equation:

d: Distance the ball falls

Vo: Initial velocity of the ball

a: Acceleration due to Earth’s gravitational pull

t: Time at which the distance is considered, with t=0 being when the ball was released.

For scientists, everything is subject to being disproven. If you could produce a repeatable test, confirmed by peer review, where one lets go of the ball and it doesn’t respond according to the equation above, you could re-write the physics books in every high school, not to mention haul in a Nobel Prize in physics. The scientific pathway for doing that is available to you. Just find the example that contradicts the theory of gravity. I’m not saying it’s likely, then again, at one time everybody just knew that the Earth was the center of the universe, right?

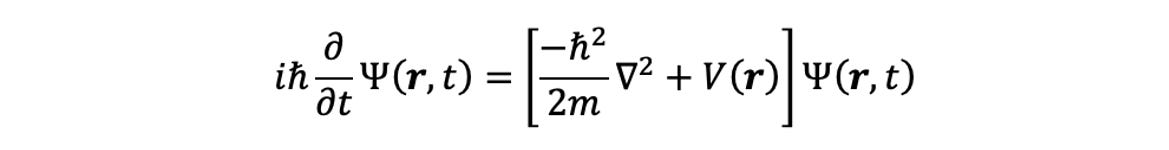

Since the intellectual awakening brought about during the Renaissance, scientific progress has come a long way beyond simply describing the movement of a dropped ball. The Schrödinger equation defines the probability field of an electron existing in a particular place and how much energy it has as it orbits around the nucleus of its atom:

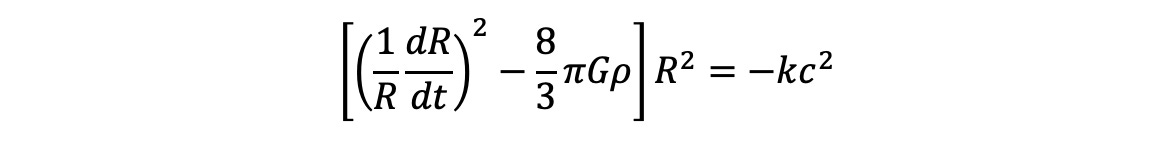

Maybe you’ve heard the universe is expanding at an accelerating rate. We’ve got an equation that describes that as well – The Friedmann equation:

Science can describe everything from the infinitely small to the infinitely large and everything in between. Once these revelations are discovered, the scientific community scrutinizes, analyzes, tests, re-tests and then finally accepts – as a theory. A theory is the best description of the world around us until someone comes along with data that contradicts it. When that happens, it’s back to the chalkboard to come up with a better theory that describes all the data, including the new data that vanquished the old theory. This process of working our way from observation to working theory is the Scientific Method, and the engine behind the astounding advancement in the scientific world over the past few centuries.

Meanwhile, political science has progressed as well, but on a somewhat different trajectory. For large portions of the world, feudal states have been replaced with complex societies governed by some form of democracy. Even among the democracies, there is a fair bit of diversity. The three branches of government and two political parties in the U.S. works reasonably well, but so does Germany’s multi-party parliamentary system. Digging deeper within the political landscape of a place like the U.S., you’ll find the political evolution seems to have stagnated. Incessant battles rage on generation after generation over a broad variety of topics. The scientific method has prompted us to discard flawed ideas in favor of ideas that better explain the world in the realm of traditional science, but it seems not to have caught on for political science. Scientists have long ago concluded that the Earth revolves around the sun and not the other way around, but there’s no consensus among politicians to trust climatologists about climate change. If there was ever a clear-cut indicator that our society is stuck in a political cul-de-sac, it is the existence of the CNN show, Crossfire. When Jon Stewart came on the show and called out the show’s hosts for promoting division and conflict rather than trying to find solutions, it was groundbreaking. It was newsworthy. And yet, it was largely ineffectual.

16 years later after Stewart’s appearance on Crossfire, we still suffer from two sides bickering, talking past each other, looking to score political points, but never searching for evidence to determine if their point of view is justified. We have become a nation filled with people far more concerned about protecting their political ideology than improving upon it. In a world where an infinite supply of information is a few keystrokes away, it’s inexcusable that we can’t start to differentiate political truths from fantasy and narrow the field of factually-viable ideologies in this world. We have given the politicians far too much free reign to run rampant with ideologies that lack the support of the scientific structure that would limit unsubstantiated and irrelevant arguments from persisting. Surely, if we considered these political science issues in the way the rest of the scientific community has dealt with their areas of study, we might arrive at some political truths – or at least theories we can all agree work the best at describing the political world around us.

This book endeavors to address this deficit of a factual foundation in our politics by evaluating many of the hot-button issues of the day through the lens of the Scientific Method. We should not accept, for example, the notion that tax cuts for the rich pay for themselves simply because that’s what we’re told by our politicians. This is something that can be researched to determine whether this has been, in fact, the case the previous times it was tried. If the facts support that assertion, then low taxes for the wealthy should thrive in political discussions across the nation. On the other hand, if the facts contradict that assertion, it should be discarded on the historical trash heap of experiments that didn’t work – never to be tried again.

In writing this book, I feel like a sculptor. Starting with a blank column of marble, I chip away all that doesn’t belong. By considering all the relevant arguments surrounding an issue and discarding those that are contradicted by facts and logic, what’s left behind are the ideas worthy of being considered a political working theory.

This approach is consistent with the Scientific Method if I can be trusted to present all sides of the intellectual debate in “good faith”. It will not take long for you, the reader, to recognize that I have a bias that would be considered “liberal” by today’s standards in the U.S., so I may as well acknowledge it up front. My ability to analyze these topics objectively is inherently hampered by my natural inclinations. Nevertheless, I have made a conscious effort to be as objective as I can in writing this book. That said, I can only write about that which I am aware of. I am well aware of the liberal arguments used in an argument, but it’s possible that I’ve not yet become aware of compelling conservative arguments.

In my desire is to present a purely factual book, I’ve taken steps to mitigate the risk of presenting an inordinately biased book. As you’ll see in the next chapter, I have deliberately spent a lot of time engaging with people with views different from mine in an attempt to understand their point of view. I wanted to understand why they believe what they do, and their views are reflected in this book. Upon writing the first draft, I’ve put the manuscript in the hands of friends and family that are more conservative than I am in search of arguments that I might not have been aware of. Their feedback is included in the pages that follow.

While most other books that line the politics section of bookstores are written by partisans trying to pass off their views as the truth, I endeavor to present the truth and let the chips fall where they may. Nevertheles, it is unavoidable that the end result reads like a partisan book.

What can I say? It seems that facts do indeed have a liberal bias.

If, after rejecting hypotheses due to contradictory evidence, there are no remaining conservative arguments that survive scrutiny and all that is left standing are the liberal arguments (because the facts support them), then we must conclude that the path forward is the liberal take on things. I’ve not deliberately omitted any compelling conservative arguments, but it is entirely possible that I have missed compelling arguments from the conservative camp that would provide a thorough rebuttal to the liberal arguments. If such arguments were to come to light, one might think that I would view such a revelation as a disaster, as it would undermine this entire book. On the contrary, I would welcome being informed of compelling factual information that contradicts my current beliefs.

The last thing I want is to believe things that are not supported by facts.

If there are arguments that contradict the conclusions drawn in this book, then I want to know if it. My interest is in ensuring that the political future of this country rests upon a foundation of facts and logic much like the scientific world has. I’ve made a deliberate effort to understand “both sides” of the argument over the past 7 years, and the book that follows is a good-faith presentation of what I have learned. If you disagree with what follows, I invite you to contact me through the publisher and enlighten me with the factual evidence that contradicts the conclusions drawn here. Until then, this is the truth – or at least working theory – as I know it.